Apple Award Winning Podcast

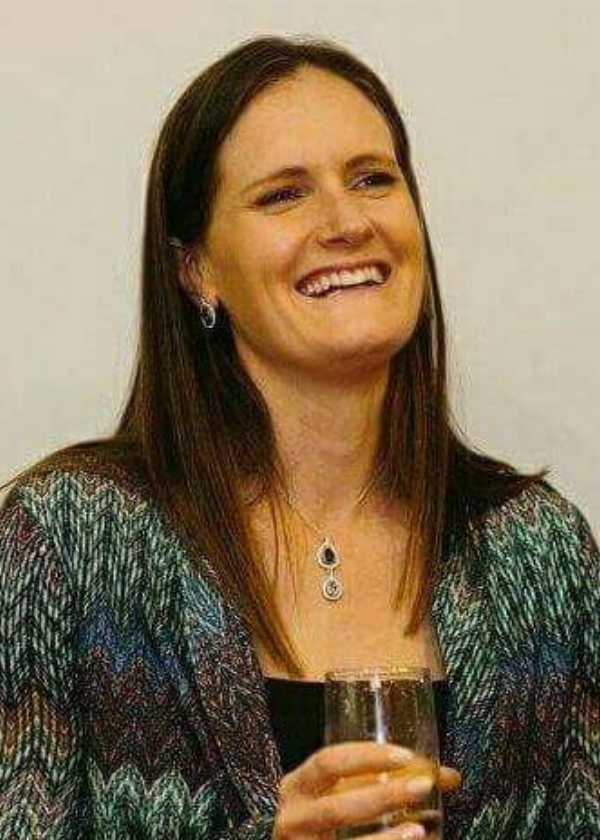

Bronwyn Louise Brooks is a family advisor in the funeral industry, and today we explore the role of empathy in listening. Bronwyn deals with conversations at the end of people’s lives. This role has given her an extraordinary sense of empathy and lack of assumptions. She has to display absolute presence when helping families make the difficult decisions when emotions are high and people are vulnerable. This was probably one of the most transformational interviews that I have been a part of.

Tune in to learn

- Bronwyn shares how she does her job and creates space for people to decide what they would like to do.

- How Bronwyn knows the pain and depth of sadness of losing a loved one.

- Bronwyn shares her childhood and background and how she lost her brother when he was 15.

- Bronwyn also shares her cancer diagnoses when she was 14 and how it was a life changing experience that helped her mature.

- How Bronwyn became involved in the Make a Wish Foundation. She also shares her life changing experience in Nepal.

- How Bronwyn’s brother seemed to be doing well before his suicide.

- The role of silence and the questions that Bronwyn answers for people.

- The importance of not only listening to the words, but also understanding the meaning of the words as expressed by that person.

- Doing your best is the last thing you can do in the person’s honor.

- The balance between it being about the person and for yourself as well.

- How it is important to listen from a place of real genuine interest.

- The opportunity of hearing the story of what people have been through.

- Being present with people as they make necessary decisions to remember their loved one.

- How the death of a spouse after a long marriage of 50 plus years can be very emotional.

- Bronwyn is all four listening types. We can all be a lost listener when we are preoccupied. There is a real art to being present.

- Always take a deep breath before walking into a room and meeting with someone.

- The 5Rhythms dynamic movement process and Gabrielle Roth.

- How everything we do in life leaves a rhythm.

- Listening is not about you, it is all about the other person.

- The importance of building a connection, dropping assumptions, and being present and available.

Links and resources

Transcript

Podcast 012: Deep Listening with Bronwyn Louise Brooks

Oscar Trimboli:

Deep Listening, Impact Beyond Words.

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

I often use the analogy, back to the funeral director world, how many people come into me and would say “I just want to put mom in a cardboard box,” and that was really, really common. Learning how to have that conversation with families, what do they mean by putting mom in a cardboard box? Often that means they don’t want to spend a lot of money on a coffin. The company I worked for, I had a range of cardboard boxes, which actually cost more than the hardwood coffins.

Finding out, was it an environmental reason that they wanted to put their mother in a cardboard box? Just having that conversation, I thought that was another example of listening and working out, what are people’s reasons behind what they’re saying, and is what they’re saying what you think they mean?

Oscar Trimboli:

In this episode of Deep Listening, Impact Beyond Words, we speak to Bronwyn, who deals with conversations at the end of people’s lives. Bronwyn works in the funeral industry, and in this episode, listen out for the extraordinary empathy, lack of assumptions, and absolute presence that Bronwyn displays when she’s in dialogue with people discussing how to treat their loved ones when they’re passed on. I wasn’t sure what to expect, but what I found was it’s probably one of the most transformational interviews I’d ever been part of. Let’s listen in for Bronwyn.

Please explain to the audience what a family advisor does.

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

I work at a crematorium in a cemetery. I meet with families that have had their loved ones cremated here, and I had conversations with them about what they would like to do with their loved one’s ashes. Some people choose to collect the ashes, and either keep them at home for a period of time. They might like to put them in an urn on the mantel piece. They might like to put them in some jewellery, or other kind of keepsake options that the families choose from. Other people want to take the ashes out to sea, or spread them off a mountain top.

There’s lots of different ways that the people go about that, and some families choose to memorialise here, in the park where I work. That might be in a brick wall mesh, or in a family garden. There’s lots of different memorial options for people, but I guess what I enjoy about my job, and what I find gives me satisfaction, is just creating space for people to consider what they’d like to do, and give them the time to know the options, because until you’re in that situation, you don’t know what is available to you. Before I did my current job, I was the funeral director.

A lot of people say to me “Oh, how do you do that?” I just say “Well, I can sit in the room with someone, and just be so grateful that I’m not in the shitty spot that they’re in right then and there.” I genuinely know how horrible it is to be in that physical pain, and that depth of sadness that losing a loved one creates. When I’m in a room with someone that’s been in that spot, right then and there, I can just be present with them, and be grateful that I’m not there now.

Oscar Trimboli:

Where did your story start?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

I was born in Melbourne. I was the second of four children, so… big sister, little sister, me, and my brother Steve. Steve is no longer with us, he died from suicide when he was 15, and I was 17. When I was only eight, I got diagnosed with ovarian cancer, so while that was a challenge in itself, it also allowed me to step outside of the normal schooling system, and I ended up at alternative schools, speaking at 9 and 10, and completed my Victorian Certificate of Education for my final two years of schooling at Foxfield Hayes.

That allowed me to enter the workforce, started working full-time at 17, and was doing my final best year subjects at Hayes during evening classes. I guess having cancer as an adolescent… yeah, it was life changing, because… probably a mature kid from the start, but that time away from mainstream school in the hospital environment, and having to relate to nurses, and deal with people that were older than my peer group meant that, it was an avenue for me away from the mainstream schooling.

I think I thrived off of not having to conform, and follow the standard steps of the education system. I think I would have found that a challenge, and having cancer created another alternative pathway for me.

Oscar Trimboli:

Was it at that point in time that you intersected with Make-A-Wish Foundation?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

Yeah, the Make-A-Wish Foundation I learned about through canteen. I got very involved with the support organisation for young people living with cancer, and after receiving a lot of support through their peer and teen programmes, I became president of the organisation at 17… well, president of Canteen Victoria, and there were other kids there that were getting these wishes granted, and I had never seen myself as being sick enough to have a wish granted, but they came and visited me in the hospital. At the time, my auntie and cousins were over in Iraq doing missionary work over there, and I desperately wanted to hang out with my cousins. That was my wish, to go and visit them.

I remember the Make-A-Wish Foundation saying, “There’s no way we’re sending a kid that’s having chemotherapy treatment over to Iraq,” and I said, “That’s cool, no dramas, that’s fine.” They said “Well, don’t you want to go to Disneyland, or don’t you want a new bedroom suite?” Other popular childhood wishes that other people had had granted, I said “No, I want to see my cousins, and that’s cool if we can’t do that,” but that’s what I really, really wanted.

The plan came to meet my cousins. There was an annual conference that they attended every year, and that all came to happen, so off to Switzerland I went. My whole family got to come with me, and that was just an incredible, incredible opportunity.

Oscar Trimboli:

Did the Make-A-Wish Foundation spark an interest in other cultures for you?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

Yeah, absolutely. I certainly really wanted to explore the world around me, and had thought India would be an awesome destination. I’m still yet to go there, but I was working at McDonald’s as a teenager, and heard on the radio that the Millennium Expedition for young Australians were taking a group of 100 people to Nepal for an expedition, and Triple J just had it advertised all the time. I made inquiries, and you had to be 18. This is one of the occasions that I called on the cancer card, and put together an application, asking if I could go.

Everyone that went, they selected 100 young Australians, so the application submission was something that everyone had to do. Mine was just an exception because I wasn’t quite 18. Once they saw the cancer girl thing, they said “Yep, you can come, if we can have a film crew for you around.” That got me there, and that was really, really life-changing. I’m still friends with people that I met over in Nepal. We were there for seven weeks doing… we did a little bit of trekking, but we also had medical clinics over there, doing leprosy clinics, an eye cataract work, and a building project as well. Certainly, the poverty that we witnessed there, and the extreme living conditions, was a real-life eye opener for a 17-year-old.

Came back from Nepal, and it probably wasn’t long after that, that my brother’s health declined. He was admitted into an adolescent psychiatric unit, which was a pretty rough time to my family. My older sister was studying her final year, 12th year. My younger sister was young, she would have probably been in late primary school, maybe grade five or six. My brother was just not coping very well, and beginning to get quite unpredictable in the family home. It was decided that for his safety, and the safety of myself and my siblings, that the psychiatric ward would be, I guess, an option.

Yeah, that’s where he went, and like a lot of fat people that die from suicide, I think it’s quite common you’ll hear people say how well the person was doing in the lead up to them passing. By that, we had… there had been times in Steve’s life where we were kind of aware that he wasn’t doing well, and we would be on a close look out for him. But certainly, immediately before his passing, we were all pretty relaxed, and were feeling that he had turned a corner and was in a good place. That’s quite a common theme that I hear, is hear from other families that have experienced suicide in the family.

Oscar Trimboli:

So, life goes on?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

Mm-hmm (affirmative), it does, yes.

Oscar Trimboli:

What happened next for you?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

I think the melee is between my cancer, my recovery from that. It’s kind of blurred between that thing, obviously a big old deal. I feel like we kind of jumped from that straight into my brother, and it was just a really full-on… probably 10 years, where I just was exposed to a lot of really traumatic experiences. If I say from 14 to 24, it was… I attended a lot of funerals in that time, and I was exposed to a lot of grief and sadness. I look at now, I’m 33, and I look at the last 10 years of my life being a lot more joyous, a lot more to celebrate. A lot of happy times then.

Oscar Trimboli:

Talk us through the role of the kinds of questions you answer for people, and the role of silence for you as well, in helping people making the decisions that matter.

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

I think you need to be able to be comfortable in silence, in a thought. Don’t have words, there are no words that I can say that can help at all, so just being there and waiting for the right words to come. They don’t always … I think, when you meet with someone, there are so many other ways to communicate, other than words. Body language is important. Just yesterday, I took a lady for a tour of the park here, and she kept saying to me how much nature was important to her. I took her to where we have a really lovely creek, and lots of bush rock, and palm trees. It’s a really serene part of our park. I’m attracted to that area, because I feel like it’s really close to nature, but what she actually liked within our park was not that area at all.

She liked an area that had more granite, and was more formal, and more… not nature, but more gardened, more tended to, more formal, I guess. Yet, when she was in that, she kept confirming that “Yes, this is what I like, because I like nature.” It was just an example for me, just to… a little reminder for me to kind of go after her. She was still referring to that space as being in nature, and she liked that area because it was close to nature, yet my image in my head when she said nature was not what she had, it was the creek, and the bush rock, and what I would thought as more of a natural setting. Listening to not only the words, but trying to understand what people mean with their words, is really important.

Creating an outcome where someone walks out of our care happy… not happy, happy is not the right word, but content maybe? I think you want to do your very best when you’re putting together a memorial for someone that you love. You want to make sure that you’ve done your best for them, and often you feel like it’s the last thing you can do in their honour. It’s about them, but it’s often for you as well, cause it’s a place where you’ll go to remember, and think, and contemplate. It’s that balance between it being about that person, but for the living as well.

Oscar Trimboli:

Great insight onto the fifth level of listening, which is the meaning people make from the same conversation. Both people can hear the same words, but make totally different meaning from the same conversation. I love the way you talked about the role assumptions play as well, in helping to either hold the conversation back, or move it forward. What do you think is one thing others could learn, that the funeral industry does well around listening?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

I think it’s just important to listen from a place of real, genuine interest into that person’s life. I think that’s what I find so fascinating about what I do, is just the opportunity to hear stories of what people have been through. I think everyone has a story, everyone has a story. I find that really, really interesting, looking at someone that’s past 100, that lived through two world wars. The advances in technology, and how they’ve adjusted to life, from horse and cart right through. I think that’s just absolutely incredible. There’s no two people the same, there’s no two families the same. I think in my role as a funeral director, it was an absolute privilege just to be witness, and be a part of families’ lives at a time of huge significance, really. Be present with them as they make necessary decisions that they need to make to remember their loved ones on the day of their funeral.

Oscar Trimboli:

Is there a story you remember listening to that really stands out for you?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

There are lots of amazing moments and stories. People would always say “How do you do children, and how do you do young moms that have died of breast cancer?” Don’t get me wrong, those days are really tragic, and are hard. It was often for me, when you were looking at the situation of someone that had been married 50 plus years, and they were saying goodbye to their spouse, and could potentially live another 10-16 years without that person. That was always a trigger, I always found that really emotional.

I think on the days where you did have a large number of people, they tend to come to the younger people’s funerals. You’re so occupied with the task at hand, of conducting the funeral, often it was the days where you have a smaller group there, and the husband’s saying goodbye to his wife. You just look in his eyes, he’s an elderly man, and you look at the pain there. It’s kind of what we all aspire to, isn’t it? Live happily ever after, and have a long, healthy life. But I guess it has to come to the end for everyone.

If it happens when you’re young, that’s obviously tragic, but the sadness associated with death at an old age, and the loss to the person that goes before the other, I think is… it always got me, anyway. Always pulled at my heart strings, that one. Especially that my grandparents are still alive, and I look at the two of them and kind of imagine one without the other.

Oscar Trimboli:

Well, we’ll change pace a bit now, and we’ll talk about the four villains of listening: the lost listener, the shrewd listener, the interrupting listener, and the dramatic listener. Which one of those listeners frustrates you the most?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

Probably the dramatic listener.

Oscar Trimboli:

What is it about the dramatic listener that really frustrates you?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

Just that they’re making it all about them, and not the person who’s telling the story, the person in front of them.

Oscar Trimboli:

And which one of those four listening types do you think you might be?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks

I think I have a tendency to be awful.

Oscar Trimboli:

What situations do you find yourself in that you’re one of those, mostly?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

I think that we can all be the lost listener. I think you can be just busy and preoccupied, and there is a real art. Two, being present, and I think in my job, and this industry, when you can be dealing with a number of different families at different times, one of the skills we have to have is to be able to be present with the current family that you’re dealing with at that moment, to leave behind you any of the other communication or work that needs to be followed up with, with other people. Focusing on the one task at hand is important.

Oscar Trimboli:

What advice would you give to others from your own practise about how to prepare to be present? Are there any tips or tricks you do to prepare in between those various conversations, so you are present for those people?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

Don’t walk into a room to meet with someone, until you’ve taken a big, deep breath. A lot of it’s to do with organisation and preparation. I’m a firm believer that you’re better off letting someone wait for five minutes, and making sure you’ve made all the notes you need to. I see you can’t be present when you went to that room, but I think a step before that is just to not, when possible, not to over-schedule yourself so that you can be there for everyone when you need to be.

Oscar Trimboli:

Right, you talked about taking one deep breath. How conscious of your breathing are you before you go into the room, and during the conversations?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

I think I am quite conscious of breath. I do something called five rhythms, which is a moving meditation dance practise. That certainly carries me through all aspects of my life. Really interesting, actually, Gabrielle Roth created it, and in the… It talks about how in everything we do in life, we leave these rhythms. The rhythms are a staccato, chaos, flowing, lyrical, and stillness. I use that moving meditation dance practise as a backbone for life, really. I dis the Ironman 2015, and there would be times that I’d be swimming and riding, and I would be visualising those rhythms, as I did each one of those activities. On race day, I would tap into chaos, or tap into staccato, which is very regimented.

Oscar Trimboli:

If I was to say, what question haven’t I asked you about listening from your background, that you think others would benefit from, what would that be?

Bronwyn Louise Brooks:

I often use the analogy, back to the funeral director world, is that so many people come into me and would say, “I just want to put mom in a cardboard box.” That was really, really common. Learning how to have that conversation with families, what do they mean by putting mom in a cardboard box? Often that means they don’t want to spend a lot of money on a coffin. The company I work for, they had a range of cardboard boxes, which actually cost more than the hardwood coffins. Finding out, was it an environmental reason that they wanted to put their mother in a cardboard box?

Just having that conversation, I thought that was another example of listening, and working out what are people’s reasons behind what they’re saying? Is what they’re saying what you think they mean? I think listening is… remember that it’s not about you, it’s all about the other person. There are so many different ways to do a rapport, and gauge connection. When you can still the mind, and drop the assumptions, just check into the space, be really present and available to the other person, you just never know what you’re gonna learn about them.

I think that’s the starting point of where you base your connection from, with an open mind, and an openness to just see where it goes, what you can find out and learn from another person, regardless of their age or their belief, whatever their background.

Oscar Trimboli:

It’s been so fascinating listening, and learning from you today, Bronwyn. Thank you.

Oscar Trimboli:

What a privilege it was to listen to Bronwyn. What I found extraordinary is the way she described the fifth level of listening, listening for meaning, particularly the example she used, when she was talking to somebody about the outdoors, Bronwyn’s interpretation of a beautiful environment and her client’s were very different, and the meaning they made from the same conversation was totally different.

I hope that prompted you to think about, are you taking the same meaning out of a conversation that the person you’re listening to? How can you confirm that? One of the ways I do that, is I ask during the conversation, “If this story was a book or a movie, what would its title be, and why?” It’s in that question, that they discover their own meaning. But more importantly, they communicate that meaning to you, so both people in the conversation have the same meaning.

At the fifth level of listening, listening for meaning, we help people make sense of the stories from their past, so they can write the next story: the story of their future.

Thanks for listening!

Oscar Trimboli:

Deep Listening, Impact Beyond Words.